Ostensibly EFL exams are simply tests of linguistic ability. But they are not just that. They are themselves a form of political education, although this may seem a rather grand term to describe the way they oblige people to adopt particular attitudes to texts in the exam. The way we deal with texts in the classroom is part of the way youngsters are prepared for the political culture they will participate in in adult life – a culture which may be more or less authoritarian, more or less conservative. Now, what sort of preparation do younsters get from the way texts are dealt with in EFL exams? To sum up the effect: The youngsters get the message that all the marks go to those who are uncritical and efficient and unconcerned about leaving the world exactly as they find it. If it were just a matter of an exam taken only once and lasting only a few hours, this would be insignificant, but the expected exam usually sets the tone for the entire course so that teachers and writers of EFL materials oblige students to adopt the same dubious attitudes in virtually every lesson. Of course, if the EFL course were the only influence in this direction, it could safely be ignored, but it is far from being the only influence.

The political conservativism of EFL exams is evident in their treatment of texts. Firstly, there is the choice of texts, which tend to stick to a presentation of the facts about something: the latest statistics or the findings of the latest research, for instance. In a recent ECCE paper one reading passage was about the marriage customs of the Amish – a passage sticking strictly to the ethnographic details of what is customarily done. In its place the University of Michigan would never have chosen a passage expressing a controversial opinion about the importance of preserving the old customs or about the decay of the traditional family or about the value of monogamy or about the role of religion in marriage. No, the texts must stick to the incontrovertible facts.

And what do students have to do with these texts? Don't the texts touch on issues – albeit ever so tentatively – that the student ought to have an opinion about? Doesn't the writer make claims that the student could agree or disagree with? Doesn't the student have a whole world of experience and understanding in terms of which some parts of the text could have a powerful appeal or persuasive force and others not? But in EFL exams such considerations – it seems – are irrelevant. The questions do nothing more than ask students to accurately discern the facts – not compare the claims of the text with the facts of the matter, but just identify the facts as described by the author, whose authority and veracity are never called into question.

Then there is the influence of the time constaint in EFL exams. The Michigan ECPE is probably the worst culprit, expecting its candidates to get through questions at the fastest rate of knots. Throughout their course students will have to be trained to cope with exams like these, and with EFL texts they will have to develop the habit of reading fast – of looking for the answers and then moving on without a second thought. What this entails is that students learn to be uninterested in the texts. Students have to take no interest in the texts. They have to lose the expectation that a text might be interesting otherwise when it proves to be uninteresting they will be disappointed and will lose the frame of mind required to tick the right boxes at the maximum speed. Students must perform the task allotted to them as efficiently as possible, ignoring any exquisite turns of phrase that less efficient readers might linger over and ponder.

Marshall McLuhan once reminded us that the invention of printing and the emergence of a culture of the written word gave rise to a more critical mentality – a mentality that was foundational both for what we call the Enlightenment and liberalism. People could privately reflect on arguments in print without the forceful presence of orators and cheering crowds. In a quiet room of one's own texts could be compared and arguments weighed up in a process that also deepened the individual's self-assurance as someone with a mind of his own – as someone with a right to say 'yeah' or 'nay' to the prevailing opinions of the day, and as someone with the ability to see through the idiocies that pass for conventional wisdom.

Ambassadors of the English language who also know of the connection between the written word and the enlightened culture of critique are inevitably a little disappointed that EFL classes – under the influence of exams designed according to bureaucratic and commercial criteria – so readily encourage youngsters to become both uninterested and uncritical – content to leave both texts and the world exactly as they found them.

Showing posts with label schooling. Show all posts

Showing posts with label schooling. Show all posts

Wednesday, 27 August 2008

Friday, 22 August 2008

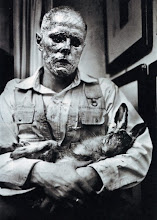

How to Break a Child

We recommend that if teachers and trainee teachers have not yet read Herman Hesse's "The Prodigy" they really ought to. It is a classic story of how a child is broken. Admittedly the book deals with an extreme case: an exceptionally gifted child who ends up floating down a river after what might have been suicide, but the story has a much more general significance. It is not only the brightest children who can be broken, and to be broken doesn't mean you are on the verge of ending it all. Since these milder forms of breakage are so common, Hesse's story can be taken to illuminate a very broad swathe of educational practice.

So how do you break a child? It is really quite simple. Here are a few steps you can follow:

1) First you need to command the respect of your pupil. You must stand tall and proud (albeit a little stiff) and ooze knowledge. It must be clear that you are the conduit to a world of learning that, as yet, the child can only look up to and marvel at.

2) You must also endeavour to be likeable. Approach the child personally with a warmth that reassures her that this is where she belongs. Only if there is this personal touch will the child end up wanting to please you.

3) From the earliest lessons ensure that every piece of work the pupil does is marked. Record all the marks and then make their sum total the focus of the report to the parents. The child must learn that it is the marks that really matter, not the work itself.

4) Then, as gently as possible, you need to raise the issue of the child's progress. She must appreciate your concern about whether she is achieving her true potential. Perhaps she could aim higher and do more? The child needs to see that achievement is everything.

5) To twist the knife a little more it helps to draw a few comparisons between the child and her peers. How close is she to being top of the class? Could she not be closer? Surely she doesn't want to let the others beat her?

6) In doing all this you will inevitably point occasionally to the clock and calendar and stress the fact that there is no time to waste. The child's young age is no excuse for allowing valuable time to be squandered on childish pastimes. It might once have been fun to run through the fields and play with the goats or make daisy chains in the sunshine down by the river, but the time for that has now passed. We must concentrate on trying to get ahead and, as they say, "Time waits for no girl".

7) Don't forget to keep showing you care. As well as a warm word and a tender hand on the shoulder, don't miss the opportunity for an occasional gift. An extra photocopied worksheet perhaps, or a book for the "holidays" or (best of all) some extra lessons at the weekend at no extra cost. The child will appreciate the gesture and will strive so much harder to come up to your expectations.

Remember, though, that throughout this process the teacher cannot guarantee perfect results from her efforts alone. At the very least, the cooperation of the parents is also required. Fortunately they are such accomplished accomplices in this loving process of psychological erosion. How often have we been told by the poor girl's parents to be firm with her? The girl is lazy and bored, apparently, and the advice is to get firm. Give her a good telling off. Embarrass her in front of the rest of the class. That will snap her out of her old ways. It's for her own good after all. She has to see that her future success is at stake. Although we have tried to emphasize how the process can be made as sweet and painless as possible, the parents are right to remind us that fear can be just as effective, if not more so. In the end, if all goes well, your efforts will bear fruit. A number of children will reach the point at which the most important thing in their lives is the recognition they get from you and from the educational system's official panel of judges. To come out on top or be given a distinction or at least to get a certificate and be one of the winners - that is what matters. Such children have been so perfectly moulded that their self-esteem is entirely a function of the educational system's estimation of them.

What can the child look forward to as a result of all this conscientious schooling? It depends. Those who do actually come out on top are likely to be channeled into other areas of achievement, both academic and professional. Since they are the winners there is no excuse for them not feeling good about themselves, but won't there be a certain hollowness to it all? With their sights set exclusively on the target, the goal, the peak, the accolade isn't there a risk that they will forget to make the way there as pleasurable as possible? Peaks are wonderful places and the views are magnificent but they aren't places where you can stay long. After the congratulations and the photos the descent begins. If the peak is everything and you can enjoy neither the ascent nor the descent something has gone sadly wrong.

The winners also find themselves on a treadmill that has a curious momentum of its own. As it turns, a doubt starts to gnaw again at the back of the mind: could I not be better? With that doubt there will be a perpetual need for reassurance, again in the form of some official recognition. No one can rest content after putting a single trophy in the glass display cabinet and believe forever that they are a winner.

Things are much worse though for the majority who, for one reason or another, do not find themselves amongst the cream. They are likely to feel not that things have a hollow ring but that they have been left with a completely empty husk. The child who believes that her estimation of herself is nothing more than the system's estimation of her cannot but draw the conclusion, when she fails, that she is indeed a failure. No one need say anything. The result is enough and the conclusion follows logically.

How could they possibly find the psychological strength to brush aside the ruthless judgment of the system and make their own assessment of the path that they have taken? Having been robbed of their own power of judgment, how could they possibly look back and say, "Despite the result, it was worth it"?Of course, in a sense, there are still things to go back to - old sources of pleasure. There are still daisies down by the river. But even if the girl can go back to them, she will find that they have been changed utterly. They are no longer what they were, now that the judgment of their inferiority and insignificance has become so ingrained.

The outcome is almost never as tragic as the one in Hesse's narrative. People find ways of muddling through and the indoctrination is rarely so complete that nothing whatsoever can console those who don't come up to scratch. Parents are never as single-minded as the father in the novel, nor are children as isolated from supportive friendships as the child prodigy. And society is much more welcoming for those who don't make it into the fast stream. After all, it is full of places for the legions of the browbeaten and downtrodden. Look how quietly they take their place and uncomplainingly play their humble part.

They are welcomed and they take their place, but still their life has been lessened and damage has been done that cannot be undone. The child who was full of herself, taking pleasure in the wealth of the world, has become an adult somewhat emptied, somewhat broken.

So how do you break a child? It is really quite simple. Here are a few steps you can follow:

1) First you need to command the respect of your pupil. You must stand tall and proud (albeit a little stiff) and ooze knowledge. It must be clear that you are the conduit to a world of learning that, as yet, the child can only look up to and marvel at.

2) You must also endeavour to be likeable. Approach the child personally with a warmth that reassures her that this is where she belongs. Only if there is this personal touch will the child end up wanting to please you.

3) From the earliest lessons ensure that every piece of work the pupil does is marked. Record all the marks and then make their sum total the focus of the report to the parents. The child must learn that it is the marks that really matter, not the work itself.

4) Then, as gently as possible, you need to raise the issue of the child's progress. She must appreciate your concern about whether she is achieving her true potential. Perhaps she could aim higher and do more? The child needs to see that achievement is everything.

5) To twist the knife a little more it helps to draw a few comparisons between the child and her peers. How close is she to being top of the class? Could she not be closer? Surely she doesn't want to let the others beat her?

6) In doing all this you will inevitably point occasionally to the clock and calendar and stress the fact that there is no time to waste. The child's young age is no excuse for allowing valuable time to be squandered on childish pastimes. It might once have been fun to run through the fields and play with the goats or make daisy chains in the sunshine down by the river, but the time for that has now passed. We must concentrate on trying to get ahead and, as they say, "Time waits for no girl".

7) Don't forget to keep showing you care. As well as a warm word and a tender hand on the shoulder, don't miss the opportunity for an occasional gift. An extra photocopied worksheet perhaps, or a book for the "holidays" or (best of all) some extra lessons at the weekend at no extra cost. The child will appreciate the gesture and will strive so much harder to come up to your expectations.

Remember, though, that throughout this process the teacher cannot guarantee perfect results from her efforts alone. At the very least, the cooperation of the parents is also required. Fortunately they are such accomplished accomplices in this loving process of psychological erosion. How often have we been told by the poor girl's parents to be firm with her? The girl is lazy and bored, apparently, and the advice is to get firm. Give her a good telling off. Embarrass her in front of the rest of the class. That will snap her out of her old ways. It's for her own good after all. She has to see that her future success is at stake. Although we have tried to emphasize how the process can be made as sweet and painless as possible, the parents are right to remind us that fear can be just as effective, if not more so. In the end, if all goes well, your efforts will bear fruit. A number of children will reach the point at which the most important thing in their lives is the recognition they get from you and from the educational system's official panel of judges. To come out on top or be given a distinction or at least to get a certificate and be one of the winners - that is what matters. Such children have been so perfectly moulded that their self-esteem is entirely a function of the educational system's estimation of them.

What can the child look forward to as a result of all this conscientious schooling? It depends. Those who do actually come out on top are likely to be channeled into other areas of achievement, both academic and professional. Since they are the winners there is no excuse for them not feeling good about themselves, but won't there be a certain hollowness to it all? With their sights set exclusively on the target, the goal, the peak, the accolade isn't there a risk that they will forget to make the way there as pleasurable as possible? Peaks are wonderful places and the views are magnificent but they aren't places where you can stay long. After the congratulations and the photos the descent begins. If the peak is everything and you can enjoy neither the ascent nor the descent something has gone sadly wrong.

The winners also find themselves on a treadmill that has a curious momentum of its own. As it turns, a doubt starts to gnaw again at the back of the mind: could I not be better? With that doubt there will be a perpetual need for reassurance, again in the form of some official recognition. No one can rest content after putting a single trophy in the glass display cabinet and believe forever that they are a winner.

Things are much worse though for the majority who, for one reason or another, do not find themselves amongst the cream. They are likely to feel not that things have a hollow ring but that they have been left with a completely empty husk. The child who believes that her estimation of herself is nothing more than the system's estimation of her cannot but draw the conclusion, when she fails, that she is indeed a failure. No one need say anything. The result is enough and the conclusion follows logically.

How could they possibly find the psychological strength to brush aside the ruthless judgment of the system and make their own assessment of the path that they have taken? Having been robbed of their own power of judgment, how could they possibly look back and say, "Despite the result, it was worth it"?Of course, in a sense, there are still things to go back to - old sources of pleasure. There are still daisies down by the river. But even if the girl can go back to them, she will find that they have been changed utterly. They are no longer what they were, now that the judgment of their inferiority and insignificance has become so ingrained.

The outcome is almost never as tragic as the one in Hesse's narrative. People find ways of muddling through and the indoctrination is rarely so complete that nothing whatsoever can console those who don't come up to scratch. Parents are never as single-minded as the father in the novel, nor are children as isolated from supportive friendships as the child prodigy. And society is much more welcoming for those who don't make it into the fast stream. After all, it is full of places for the legions of the browbeaten and downtrodden. Look how quietly they take their place and uncomplainingly play their humble part.

They are welcomed and they take their place, but still their life has been lessened and damage has been done that cannot be undone. The child who was full of herself, taking pleasure in the wealth of the world, has become an adult somewhat emptied, somewhat broken.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)